Despite what you might infer from the government’s new Heat & Buildings strategy, the gas boiler still has a long future, says Steve Addis, Product Manager at Lochinvar.

The journey towards a net zero carbon future will involve a range of solutions – many of which do still involve the burning of natural gas.

The clue is in the word ‘net’. The priority is to reduce carbon emissions, it does not matter whether we use renewables, low carbon ‘conventional’ technologies or a combination of both because the aim is to get emissions to a low enough level where any remainder can be offset by other means – and to do it in an affordable way.

The heating and hot water sector has been lowering carbon for many years and we have the scope to go further and faster with existing technologies. Renewables will play an increasingly important role, but gas-fired heating and hot water products will be equally important.

The government’s new Heat & Buildings strategy restates its long-term commitment to low carbon alternatives to traditional heating technologies, but it does not signal the end of natural gas boilers any time soon. Yes, it will no longer be permitted to install new gas boilers in homes from 2035 as the government seeks to transition to heat pumps and other non-fossil fuel technologies, but the need to continue using a full range of carbon reducing, energy efficient solutions in both the domestic and commercial building stock will still be with us in 2050.

Established

The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) confirmed that in its advice to government when it said that the technologies and approaches that will deliver net-zero “are now understood and available to be implemented”. It did not advocate the abandonment of well-established methods for lowering carbon and advised that the transition to a lower and, eventually, net zero carbon future will depend on increasingly efficient gas-fired technologies.

These technologies also represent the most realistic, affordable, and practical approach to achieving low carbon targets without depriving end users of their everyday requirement for heating and hot water.

However, we will have to improve the energy efficiency of all buildings – that is a given. Poor energy performance is not just bad for emissions, it is often the most obvious symptom of a building that is generally not fit for purpose. Energy efficiency is also just as important as low carbon sources of power in the battle to narrow the country’s looming grid capacity gap and help us on the road to net zero.

Addressing the energy performance of thousands of existing commercial buildings can unlock millions of pounds worth of savings at a fraction of the cost of going full-on renewable. That is not to say we should not be pursuing alternative power solutions, but we can make much quicker progress if we address what we already have in place first.

Revisiting what is already installed in buildings and making sure they are working as well as possible is not only the quickest route to carbon reduction; it is the cheapest.

However, it depends on being able to gather useful and accurate ‘real’ energy consumption data that can inform a mass programme of building retrofits.

At a time when the use of digital connectivity is growing at breakneck speed and giving us unprecedented access to data from multiple sources, it is important that any information gathered about building performance is not simply logged but is turned into something that building owners and managers can understand and use to inform energy saving strategies.

Unfortunately, the way energy efficiency is currently measured in non-domestic buildings for regulatory purposes is fundamentally flawed because it looks only at primary energy and carbon emissions. It does not properly measure ‘real life’ energy use and the actual performance of the building. Part L of the Building Regulations does follow performance-based standards, but these are calculated using a ‘notional’ building which does not incentivise innovation in the design of the actual building in question.

If regulation was focused more directly on actual energy usage it would be much easier for building owners and managers to understand what is happening in their building and invest in the necessary changes. Driving greater uptake of smart metering and sub-metering is key to delivering this change.

Gas-fired systems also provide security of supply because they are not weather dependent like many renewables and, although we have continued to use a lot of gas-fired technology, the UK’s total gas consumption has fallen by 20% since 2000. A range of factors has contributed, but improvements to heating and hot water technologies have played their part.

Hybrid

The current energy ‘emergency’ leading to huge spikes in wholesale prices has starkly reinforced the need to keep improving efficiency in use of gas-fired systems. However, our sector has already made huge strides by refining the design of individual products and by using more ‘hybrid’ solutions. These involve a combination of high efficiency gas-fired products with renewables to further reduce carbon while providing the necessary capacity to meet a building’s comfort and hot water needs.

Hybrids also reduce running costs and extend the operating life of the equipment by only using the gas-fired products in back-up mode. This is another key to reducing carbon. If you have to replace products on a regular basis, you will increase your overall carbon footprint significantly.

The hybrid approach is also the only realistic way to address the most significant challenge facing our sector, which is how to minimise emissions from existing buildings. 80% of the buildings that will be with us when we arrive at our 2050 destination are already built and many would require enormous sums to retrofit to renewable only or all-electric heating and hot water. Therefore, the ability to upgrade conventional systems to low carbon equivalents will be a major step towards the net zero goal.

The replacement of gas-fired boilers with heat pumps in a care home for example, is likely to mean a complete system redesign as existing radiators would not be suitable for the low temperature heat produced. Heat pumps are significantly more expensive than gas-fired boilers and such a system redesign would involve a further substantial increase in capital cost, not to mention the considerable disruption to the residents and management.

Gas-fired water heaters will also remain important for buildings like hotels with significant peak hot water periods as they are designed on the principles of low storage with fast recovery. Heat pumps cannot provide such rapid response, which would mean a substantial increase in the amount of hot water storage required. Higher storage capacity usually equals higher storage losses and means that additional plant room space would be required. This will represent a major practical challenge.

As a result, at Lochinvar we continue to see high levels of demand for gas-fired boilers and water heaters. We have also seen a significant increase in orders for heat pumps, but usually, boilers and water heaters are being specified as well.

This illustrates the importance of being flexible and having a range of solutions if we are to continue reducing carbon while still meeting clients’ demands – and that means the gas-fired boiler is far from finished. In fact, it still has quite a race to run.

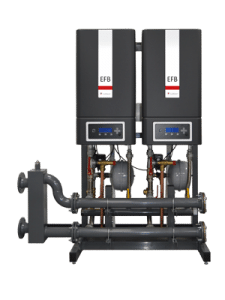

Did you know we are currently giving away a free Lochinvar Mini Fridge with all orders from our EFB and CPM range of boilers? You can find out more about this promotion here.